Economic Benefits Provided by Municipal Liquor Stores

Economic Benefits Provided by Municipal Liquor Stores

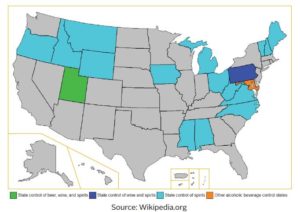

The 21st Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified on December 5, 1933, effectively repealing the 18th Amendment, and ending nationwide prohibition on the sale of alcoholic beverages. This transferred liquor control from federal oversight to state oversight. Many states immediately sought to privatize the retail sale of liquor, while several retained the ability to “control” the retail sale at the state level, including continuing total prohibition on the sale of alcoholic beverages in their states. Today, 17 control states, identified in the map below, retain some amount of government monopoly on the distribution and sale of some or all alcoholic beverages.

Soon after the December 1933 ratification of the 21st Amendment, Minnesota passed the Liquor Control Act, which was established to control the manufacture, distribution and sale of alcoholic beverages (the three-tier system that remains in effect to this day). At the time, Minnesota decided not to become a control state, but instead permitted the counties to determine whether alcoholic beverages could be sold in their communities or not. This resulted in dry counties existing in Minnesota well after the end of Prohibition.

In 1957, the Minnesota Legislature passed the city option, which allowed cities to determine how liquor sales would be handled at the city level, as opposed to the county level, with the municipality controlling the retail sales channel. City leaders soon realized that budgets benefited from this source of meaningful non-tax revenues, and the commercialization of the distribution of alcoholic beverages transformed many of the municipal liquor operations into the professionally run organizations seen today. The Liquor Control Act was re-codified by the Minnesota Legislature in 1985 into Minnesota Statute 340, which governs the laws still in effect, with 340A.601 overseeing municipal liquor operations. This resulted in certain cities in Minnesota becoming “control” cities, for which the city has a complete monopoly on the retail sale of alcoholic beverages within their city’s borders.

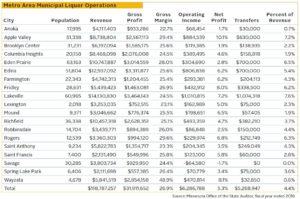

As of 2016, the Office of the State Auditor noted that there were 195 Minnesota cities (out of 853) operating 228 municipal liquor stores. Of the 195 cities with municipal operations, only 19 cities located within the Seven-County Metro Area own and operate liquor establishments. The State Auditor noted that the metro area liquor operators accounted for only 9.7% of the municipal liquor store count but represented 34.5% of total sales and 26.5% of total profits. Metro area sales totaled $118.8 million, or about $6.3 million per city; profits totaled $6.0 million, or 5.3% of sales with the average city earning $315,000. Only one city, Savage, operated at a loss, with the majority earning profits of 2.0% to 6.0%.

There are many opinions on whether cities should be in the liquor business. Proponents of free markets do not believe governments belong operating a for profit business, while the cities themselves rely on the additional income to balance budgets. However, what really matters is whether the residents and taxpayers of the cities with municipal liquor operations see some form of economic benefit from the presence of the city owned liquor stores. Measures of success in a private liquor store are return on equity and return of capital, both of which are conveyed via profits. City managers, as stewards of a city’s financial resources, have a fiduciary responsibility to generate profits from their liquor operations. Minnesota state law requires cities that incur losses in two of the last three years to hold a public hearing on the future direction of municipal liquor operations.

Returning to the State Auditor data, with the profits generated from liquor operations, cities can choose to reinvest back into the liquor operation or provide a transfer to the city’s general budget. This is equivalent to a private company making a distribution or dividend payment. Transfers totaled $5.3 million in 2016 for the 19 metro area municipalities, or 4.4% of revenues. With these transfers, cities were able to accomplish many stated tasks, such as Anoka using its transferred liquor profits to benefit the city park system, or Edina using its transferred profits to reduce the cost of city services, or Lakeville using its transferred profits to purchase equipment for the city. What often goes unstated, is that these profits are used to directly reduce the property tax burden for the taxpayers. Without municipal liquor profits, cities would need to either reduce their budgets or increase their fees and property taxes. Raising property taxes is an especially contentious topic, and thus cities utilize the profits to fund portions of the budget.

Shenehon’s independent research into municipal liquor operations revealed that in general, they do not operate any differently than a private liquor store. Municipal liquor stores must abide by Minnesota liquor laws, including opening and closing hours, follow the same three-tier distribution model, remit retail sales tax to the Department of Revenue, and cannot charge materially different prices than the private competition and reasonably expect to maintain their customer base. The entrance of Total Wine into the Minnesota market has had the single largest impact on both private and public liquor stores, with prices being lowered on all fronts in an effort to remain competitive. In our research, we found that where municipal operations differ from the private competition, is they have a larger retail store footprint, feature a broader selection of products, carry significantly less debt, and are generally more profitable than the private competition. The Risk Management Association noted in its 2017-2018 Annual Statements Study that the median profit for private liquor stores of all sizes was 3.2%, compared to 5.3% for the municipal operations.

The economic benefits afforded metro area residents and taxpayers in cities with municipal liquor stores is a lower tax burden as a result of the municipal liquor stores generating profits. They also benefit from a publicly owned asset that generates an economic return on equity and provides a return of capital, putting taxpayer dollars to productive use. Residents and taxpayers alike benefit from possessing an investment that provides for parks, streets, lights, equipment, and more, all purchased with profits generated by the municipal liquor store rather than paid for by direct taxation.